The COVID-AM blog is a partnership between the UMI 3157 iGLOBES and the Institut des Amériques, coordinated by François-Michel Le Tourneau, Deputy Director and Marion Magnan, researcher at the Institute. About the blog.

Covid-19: a threat to canadian french speaking universities?

June 9, 2020

by Serge Jaumain, Professor in contemporary history at the University libre of Bruxelles, co-Director of AmericaS – interdisciplinary center for the studies of the Americas - and a member of the scientific committee of the Institut des Amériques.

and Yves Frenette, Professor and Research Chair of Canada Migrations, transfers and French speaking communities at the University of Saint-Boniface.

In a previous article, it was noted that in Canada, the French-speaking province of Quebec was by far the hardest hit by the pandemic. Three weeks later, the situation hasn't changed: on June 4, there was already a total of 4885 deaths out of 2452 in the rest of Canada!

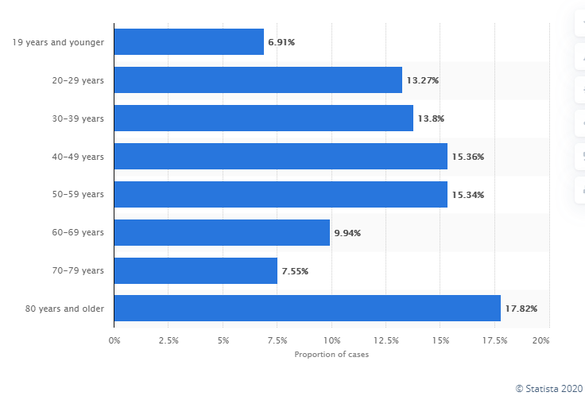

In Quebec, the coronavirus is still significantly targeting the oldest age group: 3/4 of deaths concern those over 80. Though the youth seem to have avoided this dreadful mortality rate (0.2% of people who have died were under 40), it hasn't been spared by the contamination: 1/3rd of French Canadians infected since the beginning of the pandemic are under 40.

Left: Number of Covid-19 deaths per province in Canada. Right: Number of Covid-19 deaths per age group. (June 16, 2020. Source: statista.com)

Aside from these chilling numbers, in Quebec as elsewhere, the coronavirus is affecting multiple aspects of community life: an economy on hold, a cultural sector in intensive care, a multitude of tourist and recreational events canceled, etc.

There is one sector that is rarely talked about: higher education. And yet, as in many other countries, Quebec universities and more generally Canadian ones have been hit hard by the pandemic. Right when it started, they changed to on-line teaching. Professors and students got a taste for, more or less happily, recorded classes, video interactions, remote work...In a few weeks, it's a whole new way of working that came to be. Though university resources world-wide with respect to on-line courses were very diverse, thankfully Canadian higher education institutions were ahead of the game in that area, which enabled them to "save" many students' last quarter.

However, the future seems bleak. Indeed, Quebec universities quickly understood that the Fall classes could not resume normally and, when European institutions were still hesitating, they took action, publicly announcing that from September to December 2020, most courses would be in a distance-learning format.

This difficult decision at least is clear. But it is full of meaning: as in many countries, professors worry about the impact of an education that is mainly distance-learning. Students themselves do not seem confident: during the month of May, surveys showed that, because of this, close to 30% of Canadian students were thinking of postponing their Fall registration.

To this certain decrease in Canadian student numbers, another problem is apparent: international students. As we know, Canada today is a highly attractive academic destination. For French and Belgium students doing non-degree programs abroad, these universities, and in particular those in Quebec, are the most popular. But where it will hurt the most financially is of course from foreign students seeking degrees.

Added to the local students, their cancellations could create a significant shortfall, all the more so that they usually have much higher registration fees. This situation, which will impact a lot of universities (especially English-speaking) throughout the world, will also impact French-speaking higher education institutions in Canada that are in Quebec, but also in other provinces, and that attract a lot of foreign students.

This is true for Ottawa's huge bilingual university in Ontario, located in the center of the federal capital, the small Laurentienne University, also bilingual and based in Sudbury, Glendon university campus (a bilingual campus of York University in Toronto), and soon the Université de l’Ontario français that, after a number of obstacles, should see the light in Toronto.

But French-speaking higher education is also provided outside of Quebec by small institutions in Atlantic provinces, such as the Université de Moncton in New Brunswick, Sainte-Anne in Nova Scotia and also special programs in large English speaking institutions, such as Simon Fraser University in Vancouver.

Though the expected decrease in foreign students will have financial consequences for all these universities, it's nothing compared to to what two small institutions in central Canada will face, where the coronavirus invited itself into a situation of budget cuts imposed by the provincial governments.

In the past few weeks, the survival of two French-speaking universities outside of Quebec all of sudden became the focal point of the discussions: Université de Saint Boniface in Winnipeg (Manitoba) and the Campus Saint-Jean of the University of Alberta in Edmonton. Showing a rock solid resilience, these two small institutions have been able to maintain until now a university education in French in English speaking provinces where they form essential scientific and social-cultural hubs for the survival of the French-Manitoban and French-Albertan communities.

Since the 19th century, the Université de Saint-Boniface has provided higher education in French in the town of Winnipeg. Still having close to 17% of foreign students this year, it proved itself within the scientific world as a reference for the study of French migrations in North America.

Left: Université de Saint-Boniface (Winnipeg) whose origins go back to 1818 (Source: Wikipedia).

Right: The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada funds an important program managed by the Université Saint-Boniface which includes thirty scientists from Canadian, American and European universities.

And yet, last April, in the middle of the pandemic, Manitoba's conservative government announced suddenly that all universities would get budget cuts up to...30%! Thankfully, the intense protest forced them to revise their decision, but the little French speaking institution (a little less than 1400 students) had a narrow escape because even a reduced squeeze, on top of additional costs from the pandemic and the likely non-registration of a large number of foreign students, could have had adverse effects on its services and study programs and, beyond them, for the future itself of the French-speaking minority in Manitoba.

The situation is even worse in the province of Alberta which distinguished itself recently with the financial boon generated by oil extraction (bitumen sands). It is hit hard today by the crisis in this sector and the repercussions on the university world were not long in coming. In one year, the rich university of Alberta saw its operational budget melt away by 17%, which of course had an impact on all areas of the institution, in particular the little (French speaking) Campus Saint Jean.

Alberta's French community comes together to save the Campus Saint-Jean (Source: website of the Association canadienne française of Alberta).

The budget cuts and the crisis situation mentioned above should bring about a deficit of 1.5 million CAD, which means 180 classes cancelled, representing 44% of its academic choices! Faced with the loss of this small "French speaking ecosystem" that encompasses close to one thousand students, a petition published on June 1st in the Quebec newspaper La Presse gathered in just a few weeks close to one thousand signatures specifically from researchers of main Canadian universities, worried by the potential loss of the only French speaking higher education institution in Alberta.

Even in Canada where the increase in on-line courses has become a reality for a long time, universities are therefore likely to pay a heavy price for the pandemic that has, on top of it, indirect consequences to the survival of French speaking minorities outside of Quebec. So we can understand that these little institutions should turn to the Canadian government in hopes it will intervene, as it has in other areas of the economy, to protect an essential component of Canada's bilingualism.

In this difficult period for the French speaking Canadian universities, there is however a small glimmer of hope coming from the AUF (Agence Universitaire de la Francophonie whose membership includes over 1000 universities throughout the world) that decided to transfer its Administration Office to its Montreal headquarters, based in Paris until now. During these uncertain times, this strong political gesture is one way to reaffirm the role Canada has today in international French speaking higher education.

Serge Jaumain co-directs AmericaS, the interdisciplinary studies of the Americas at the University libre of Bruxelles. He is a member of the scientific committee of the Institut des Amériques and the editorial board of the journal IdeAs. He currently heads the Scientific Council of the AUF (Network of French speaking universities). His current research is focused on the history of French immigration in the Americas. He recently co-directed a book on Les élites et le biculturalisme, Québec-Canada-Belgique – XIXe-XXe siècle (Septentrion, 2017) with Alex Tremblay-Lamarche.

Yves Frenette is a Professor and Research Chair of Canada Migrations, transfers and French-speaking communities at the University of Saint-Boniface.