The COVID-AM blog is a partnership between the UMI 3157 iGLOBES and the Institut des Amériques, coordinated by François-Michel Le Tourneau, Deputy Director and Marion Magnan, researcher at the Institute. About the blog.

Covid 19, care and contemporary chicana literature: consider vulnerability to make sense out of the health crisis

November 11, 2020

by Méliné Kasparian-Le Fèvre, doctoral student in American Literature at the Université Bordeaux Montaigne, at CLIMAS Laboratory.

Joan Tronto, invited to France Culture on May 5[1], expressed hope that the Covid crisis would give more value to caring activities: "Maybe more awareness will come out of this crisis: the need for care, the necessity for fair and equitable wages and support for nursing professions and, finally, being grateful for the care we give and the care we receive". Tronto is one of the theorists on the ethics of care, born in the United States in the 1980s, who puts vulnerability at the heart of morality and asserts the importance of care and attention toward others. The term care englobes both a disposition (worrying about others) and concrete actions (providing care). Joan Tronto and Berenice Fischer define care as "a species activity that includes everything that we do to maintain, continue, and repair our 'world' so that we can live in it as well as possible. That world includes our bodies, our selves, and our environment, all of which we seek to interweave in a complex, life-sustaining web" (40). The ethics of care therefore include an ecological dimension since attention can be extended to the non-human other.

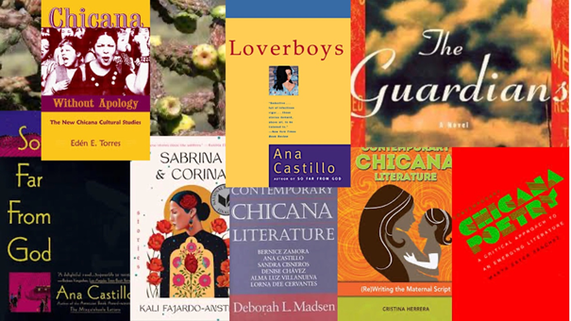

This article explores the way in which issues brought up by the notion of care are unfolded in contemporary Chicana literature. Chicana writers are American writers who have Mexican roots, activily engaged politically (they identify with the 1960s Chicano movement that defended the rights of agricultural workers, enhanced the value of Mexican American culture, and demanded educational reforms), who express themselves at times in English, at times in Spanish, at times with a mix of both languages, and explore a border and hybrid identity, both Mexican and American.

The Chicana writers' texts converse in a rather remarkable way with the theories of care by exploring facets that the current health crisis has brought to light: the unsurpassable nature of vulnerability, the importance of nursing activities mainly done by women, and the interdependence between humans and ecosystems.

The current pandemic constitutes a striking reminder of human frailty and mortality, that some prefer to ignore (the relatively weak use of masks by men for example has been tied by some researchers to a denial of human vulnerability[2]). And yet, contemporary Chicana writers focus a lot of passages on this frailty and on all the activities which are meant to fix it. Far from seeing care as an interesting task, they give it an attention worthy of that given by the theories of care, to which they echo to by presenting vulnerability not as a setback, but as a universal condition: they thus remind us that we will inevitably go through periods of dependence during our lifetime. Frailty is our destiny: "Nothing but this in the end" says the poet Ana Castillo when she watches her mother being taken care of at the hospital (I Ask the Impossible 15).

Characters who took care of others find themselves later in a dependent situation. In this way, the young narrator of "Julian Plaza" by Kali Fajardo-Anstine remembers a time when her mother, currently fighting cancer, was not sick but on the contrary gave her attention to vulnerable people: "I remembered a time when I was very little and my mother wasn’t sick. … We were visiting old people to give them pies—apple and rhubarb, strawberry and pecan. The pies weren’t for everyone, just those without family, the people who needed them most" (Sabrina & Corina 104). Here the text highlights the idea that we are all vulnerable, that we can suddenly find ourselves on the other side, the side of frailty.

Care not only points to the issue of vulnerability and interdependence, but also to all the work that makes our daily activities possible, work often discredited. We can think of nurses, cleaning ladies, cashiers particularly exposed during this pandemic, which seems to reveal for some what care theorizes: namely the importance of these workers who, often in the shadows, accomplish tasks without which the cog of the liberal world could not keep turning. Alma Luz Villanueva thus compares women who do these tasks and take care of others as cobblestones on which we walk without noticing them, their care being so basic:

the years of loving, the strength

that shielded you, like a stone

in the earth, so common, so

familiar, we step on it,

continue—but without it, the

common stone, we are homeless,

without blood, without heart,

without the common decency

to know where to place our

feet, one after the other

(Planet 12)

So care underlies our dependency when being cared for or for daily work, but also for our environment on which we depend and which depends on us. As a notion of frailty, care draws our attention on the non-human since this frailty is something we share with animals and environments. This thought matches quite well with the contemporary Chicana writers' texts which highlight the frailty shared amont living beings, interdependency between human and non-human, and the necessity for attentiveness if not sollicitude toward this last one. The novel The Guardians by Ana Castillo, dedicated to the violence suffered by the migrants and the people at the Mexico-US border at the hands of the smugglers, the traffickers, but also the authorities, opens up with a look at animal vulnerability through the story told by the narrator about the day when her female dog lost an eye by rubbing against a cactus: "Winnie has one eye now. She got stuck by a staghorn cactus that pulled it right out. Blood everywhere that day" (1).

Castillo also highlights the interdependence between humans and animals in a short story where the Miss Rose character, who is scared stiff of rats, adopts a cat that will chase them and that she promises to cuddle in return, demonstrating an awareness of interdependency and reciprocity with the animal: "It lived in the basement and fed on rats, thereby keeping the building clean and safe. Miss Rose was content with that and said that, speaking for herself, despite the cat’s unlovable appearance she would show it all the care a cat could want (Loverboys 192). The relationships with animals described in the Chicana writers' texts are therefore very close to the cosmogonies of the indigenous populations of Brazil mentionned in this blog by the Matula Laboratory: "In these views of the world, reciprocal relationships in health and solidarity between species is essential."[3].

Lastly, Castillo talks about our dependence on the environment, and particularly the necessity to take care of the soil in order to continue to pull our livelihood from it. In So Far from God, a saga on the life of Sofi and her daughters in a small town in New Mexico, the residents of Tome struggle to live off the land because of the overexploitation of the earth by those who practice large industrial agriculture: "outsiders in the past had overused the land so that in some cases it was no good for raising crops or grazing livestock no more" (139). It is this interdependency between human and non-human that this health crisis brings to our attention since it has given us the opportunity to remember that the destruction of ecosystems and biodiversity exposes us further to the risk of pandemics. Taking care of our ecosystems and the environments is essential to our preservation.

So, the contemporary Chicana writers' texts converse with the current health crisis by encouraging us to pay attention to vulnerability, to interdependence, and to the necessity to take care of others (including environments). They sketch a vision of the world where relationship (whether interpersonal or between human and non-human) is fondamental, as we can see in Kali Fajardo-Anstine's comments on the topic of her experience with the current pandemic during an interview this past May: "During this pandemic, my family, as many others, has lost loved ones. We cannot be together to grieve. We cannot get together. We cannot share meals in kitchens full of people and steam.... I found hope thanks to stories, teaching, the act of sharing what I know; thanks to books, writing, and music. ...I called my loved ones to ask them about my ancestors who lived in Colorado and that I've never known, those family members who dealt with unimaginable trials and survived them. This moment reminded me that I am first and foremost a writer, that my home can be found in my stories, and that one day, my descendents will hear about this period, in the same way that I turned to my ancestors so they could guide me"[4]. Farjardo-Anstine highlights here the importance of relationship and replaces the physical relationship, impossible during this health crisis, with a spiritual one, that reaches for the memory of her ancestors and ties the generations in a web of stories—these being perhaps the best way to care and fix.

Bibliographie :

- Castillo, Ana. So Far From God. 1993. W.W. Norton & Company, 2005.

- —. I Ask the Impossible. 2000. Anchor Books, 2001.

- —. Loverboys. 1996. W. W. Norton & Company, 2008.

- Fajardo-Anstine, Kali. Sabrina & Corina. Random House, 2019.

- Villanueva, Alma Luz. Planet, with Mother, May I? Bilingual Press/Editorial Bilingüe, 1993.

[1] Laurentin, Emmanuel, and Manon Prissé. « Joan Tronto: ‘Organiser la vie autour du soin plutôt que du travail dans l’économie changerait tout’ ». May 5, 2020.

[2] Burrell, Stephen, and Sandy Buxton. "Coronavirus reveals just how deep macho stereotypes run through society". The Conversation, April 9, 2020.

[3] Laboratoire Matula. "Discourse, experiences and resistance of traditional populations and people living in city outskirts on the dystopic world of covid-19 in Brazil". COVIDAM, Novembre 5, 2020.

[4] "A Denver Nurse, Poet and Writers Share Their Coronavirus Experience in Their Own Words-Part I". 303 Magazine, May 9, 2020.

Méliné Kasparian-Le Fèvre is a doctoral student in American Literature at the Université Bordeaux Montaigne, at CLIMAS Laboratory. Her research focuses on food motivation in contemporary Chicana literature. She published an article on the role of food in Pat Mora's House of Houses, available here.