The COVID-AM blog is a partnership between the UMI 3157 iGLOBES and the Institut des Amériques, coordinated by François-Michel Le Tourneau, Deputy Director and Marion Magnan, researcher at the Institute. About the blog.

IN Arizona, a university opening challenged by Covid-19

September 1, 2020

by François-Michel Le Tourneau, Deputy Director of iGLOBES and Senior Researcher at the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS)

At the start of the academic year, universities face a major challenge in their strategies to fight against the spread of SARS-CoV-2.

Indeed, the nature of campuses and the majority of higher education today consists in putting together a large number of people who are going to intermingle in closed spaces such as amphitheaters, classrooms and university dining halls. Furthermore, since young people often tend to be asymptomatic, the spread of the virus stemming from them can advance silently and at a larger scale, representing an important threat as soon as the students return to their families or patronize locations off-campus.

With the first phase of the epidemic last spring, most universities of affected countries hastily stopped in-person classes and opted for generalized distance learning. Though this helped maintain a relationship with the students and continue their education to some extent, we could also see all the limiting factors of that type of system, not only with respect to inequalities of access to tools, but also teaching issues.

For American universities, the return of students to campus also has a significant financial dimension. As mentioned in another article of this blog, their budget has been severely strained by measures taken in the spring and by the cascading consequences. Since the high cost of education imposed by universities on students is based for the most part on the services that are provided on campus and on the general university environment (the famous campus life experience), not being able to reopen would lead to a major crisis, if not, for the weaker ones, death.

So how can an opening that reconciles the irreconcilable - the concentration of several thousands of students on a campus and social distancing measures that help avoid the spread of infections - be attempted? That is what a team, put together by the University of Arizona (UA), worked on all summer long. Because of its leadership, the UA seems in a better place than others to confront the problem: its president Robert Robbins is a doctor, the Arizona University Covid-19 response team is led by Richard Carmona who was Barack Obama's Health Secretary, and the University has world experts in human viral pathogens, such as Mike Worobey, Department Head of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and a specialist in the flu (influenza) and AIDS (HIV).

The plan proposed by this team has now been in place for two weeks and has enabled the arrival of several thousands of students on campus. It rests on several pillars that say a lot about American universities' enormous means and adaptability.

USE OF CAMPUS RESOURCES

As most other large universities, UA has a medical program with a university hospital and cutting edge research in the healthcare field. It also has advanced expertise in technology. This combination was put to good use.

So, with the start of the semester, UA put in place large scale testing that is done right there thanks to the hospital's competence. Over 10 000 rapid serological tests (giving results in 1 hour, but with a higher margin of error than PCR tests) were done in August on students and University personnel which helped identify 372 people who tested positive and were asked to isolate voluntarily for 14 days.

Testing capabilities are also being done in an innovative way: by testing wastewater in different dorms, the administration was able to detect one of them in which two people had SARS-Cov-2, but were asymptomatic. They were isolated after all of the building's residents were tested. According to a recent New York Times article, this type of test has been adopted by dozens of American Universities.

The issue of contact tracing of positive cases also shows how American universities operate. Indeed, UA has adopted and promotes a tracing application called Covid Watch Arizona, which guarantees the privacy of its users while still being capable of informing if the user was close to someone who had Covid-19 (and had been diagnosed with it). Presented as a more or less "homemade" application, this software was in fact developped by a team put together in February 2020 around Tina White, a UA alumni, but now a doctoral student at Stanford University. The connection which is highlighted is very representative of the relationship that universities try to maintain with its alumni, who are often (when they are successful) their biggest sponsors with respect to facilities and research programs.

Just as emblematic, though it is presented as an application developped by the consortium Covid Watch, the application was built on a set of tools developped by Google and Apple's common initiative called Google/Apple Exposure Notifications[1]. As again mentioned by the New York Times, other universities opted for different solutions, for example based on the fact that students scan QR codes in order to notify the places they've been to.

On their end, on top of the Covid Watch application, UA also asks students and employees to respond to a quick health questionnaire before going to classes or the office. Called Wildcat Wellcheck (Wildcat is the University of Arizona's mascot and nickname given to its students), this test is done online or by SMS and checks for potential symptoms of Covid-19. The goal is to identify as many cases as possible, but also build a database which would provide a better understanding of how the virus spreads.

Finally, having huge buildings, UA was able to put in place a special dorm to welcome students who have gotten Covid-19 in order to isolate them from the rest of the campus until they are no longer contagious. Of course, this isolation is done under medical supervision and, if it becomes serious, the university hospital can take over.

Test, trace, treat: the strategy is clear and it rests on the assets of the University in terms of response capabilities and infrastructures.

MODIFIED INSTRUCTION, MORE FLEXIBILITY

Since holding classes in its usual format is potentially a source of contamination, several options are proposed. In-person classes are maintained for some, but with precautions: most have been moved to the biggest amphitheaters and distancing measures have been taken. Depending on the course, three options are given. Some in-person classes can be followed remotely if the student prefers this (flex in-person classes). Other classes are totally online, but require a simultaneous connection between the students and the professor (live online). Finally, some classes are e-courses which students can follow when it is convenient. This last option already existed, but now the University requires that all new online courses have some direct interaction component between professors and students. It is meant to honor the promise made to students that in-person remains at the core of the educational experience.

A staged reentry plan defines the proportion of each of these modalities. For stage 1, only classes considered "essential" and some of the outdoor classes are done in person. Though the definition of what is essential is left to each department, the informative list includes: "practical sessions in the lab, art studio or theater classes, medical (human and veterinary) and pharmacy courses and specialized classes for very small groups". At stage 2, more classes of less than 30 students will be done in-person, when stage 3 essentially represents a return to normal. Right now, the administration has decided to keep the University at stage 1 for the first two weeks of classes, postponing the move to stage 2 until further notice. In terms of numbers, stage 1 should limit the presence on campus to 5 000 students, stage 2 to 14 000 and stage 3 a return to the usual headcount of 30 to 35 000.

The flexibility offered for the classes is also true for housing on campus. UA, like many American universities, requires their first year students to stay in campus dorms and it makes extensive efforts to maintain this "customer base" throughout their studies because revenues from housing is an important source of funding for the campus. So for the upcoming year, the students can either live on campus for the whole academic year, as usual, or take a room but postpone their installation for later, or not take a room and request one later in the year. But flexibility has its limits here since for the first two options, students must pay for the whole year, even if they don't use the room in the first months. In the last option, they will only get rooms if they are available and, should they decide to not live on campus for the whole semester, they will have lost their application fees and the down payment they provided when they applied...

For housing, UA is competing with private fully equipped residences that are multiplying around campus and with the frat houses that are extremely appealing. These options which are not under the University's control regularly create behavior problems (like evenings with too much alcohol and their consequences). In the current context, they also bring up the issue of control of the epidemic since social distancing rules and gathering limits, not to mention wearing a mask, are much less followed.

Finally, still speaking of the use of infrastructures, with the campus' vast spaces and Arizona's hot and dry climate, huge marquees were put in place as an alternative to dining halls - without the AC.

CONCLUSION: WHAT IS AT STAKE FOR RETURNING TO NORMAL...

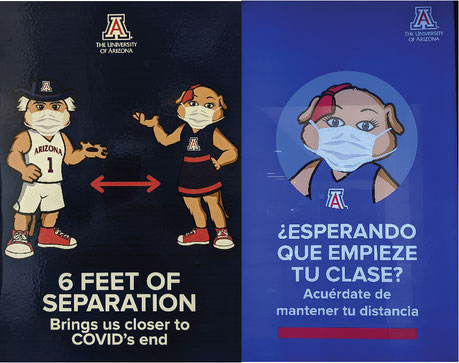

Being able to return to normal as soon as possible is a major issue for UA, as well as for all university campuses in the US. The plan presented tries to reconcile a certain flexibility with the concern of giving students the feeling that they are starting a "real" academic year, which can also be translated less poetically as "getting their money's worth" - while also providing a sense of security on campus. For that, other advocated measures supplement the health ones and those for teaching and housing: wearing a mask on campus is required, premises are disinfected more frequently, a push to wash your hands...

The issue concerning the return of students on campus is, as mentioned, financial. For UA, close to 600 million dollars are paid each year in tuition, representing roughly a third of the total budget. On the other hand, research activities are considered less dependent on presence on campus. Teams are still working from home and operating remotely, laboratory meetings are held via zoom, and the same for weekly workshops, etc. The reopening of labs, except for essential personnel and experiments, is tied to the availability of a vaccine. We shall see in the next few months whether these measures damage or not scientific output. To their credit, the general demographic of the researchers puts them in a "higher risk" group than the students. One can also see here a rather cynical conclusion on the fact that the money brought in by research will come in anyway, since most grant applications can be done remotely...

Nevertheless, and even if the disclosed numbers at the start of the semester seem to only show a slight erosion of UA's enrollment (and an increase in registration to the online educational program), having kept its main public will probably not do more than "keep it afloat" financially. Particularly lucrative activities, such as university sports, have had their 2020_2021 calendar turned upside down or postponed[2], which is likely to lead to heavy losses on TV rights, merchandizing and all the additional receivables (65 million USD are foreseen in total loss just for American football). This even impacts recrutement. One of the college football stars who was supposed to do the season at UA therefore decided to change to a university in a conference that plans to keep its fall championship...It is likely that UA, as many American universities, will still have to navigate for a number of months in a fragile health and financial environment before being able to breath easier. The university community is already feeling the pain: a large number of employees and professors have had a 5 to 20% temporary decrease in pay according to their salary range.

The current period is therefore a sort of test of resistance for the American university system. It provides an opportunity for universities to demonstrate their capacity to innovate and make use of their assets in terms of infrastructure, technology and means, but it also shows the weakness of their financial model and their dependence on tuition and external funding sources.

[1] In this context, the two companies put an API in place (a set of tools that developpers can use for their own applications) allowing for anonymous contact tracing.

[2] For now, the Pacific Conference that UA participates in has postponed the championship, when other conferences, especially the Atlantic coast one, are trying to maintain their calendar.

François-Michel Le Tourneau is a senior research fellow at the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), Deputy Director of the UMI iGLOBES and a member of the Institut des Amériques Scientific Committee. His work focuses on settlement and use of sparsely populated areas, especially the Brazilian Amazon. He is particularly interested in indigenous people and traditional populations and their relationships with their territory. He has authored a number of papers in national and international scientific journals (list here on HAL-SHS, here on Researchgate or here on Academia.edu).