The COVID-AM blog is a partnership between the UMI 3157 iGLOBES and the Institut des Amériques, coordinated by François-Michel Le Tourneau, Deputy Director and Marion Magnan, researcher at the Institute. About the blog.

the amazon, a history with no protective measures

December 16, 2020

by Stéphen Rostain, archaeologist and CNRS Senior Researcher at the laboratory "Archéologie des Amériques" in Paris. He has been working in the Amazon for 35 years, especially in Guiana and Ecuador, where he has organized several interdisciplinary and international projects, in particular using a historical environmental approach.

What would have happened if Covid-19 had started in the Amazon forest 1000 years ago? It's a legitimate question for an archaeologist. Indeed, just like its African and Asian cousins, the Amazon's tropical and humid forest is potentially just as much a cradle of unknown viruses which are only asking to erupt in order to easily spread throughout the planet. All eco-systems transformed by humans are subject to a rise of new diseases. The incredible diversity of living things in tropical areas adds a certain amount of risk of seeing surprising zoonoses come out of the great South American woods, ie animal born infections. The hosts of these poisoned gifts are also diverse, between the voracious vampire bats silently biting their prey at nightime, the vertebrate game coveted for their delicious flesh, and even the adoption of a cute little animal, such as a monkey or parrot, potentially the host of a fatal germ.

CONFINED IN THE CONFINES

We have reason to think that the first inhabitants of the silva have known zoonotic epidemics since their arrival some 13 000 years ago. A close observation of the spread and the evolution of this type of disease must have then led them toward an efficient course of treatment. Indigenous peoples have become masters at the use of plants and other ingredients in order to prepare pharmacopoeias. The very long occupation of the lowlands has given them time to develop a remarquable environmental science. Still today, Western pharmacology scientists regularly discover a remedy developped by local populations, not always grasping the required active ingredients, they are so complex and carefully put together. With close to 40 000 species of endemic plants, the Amazon has been an open luxury laboratory for indigenous savants. And, everything in the plant is good for creating a healing recipe: flower, fruit, leaf, stem, root, bark, sap, moss and shoots.

What would they have done with an unprecedented infection? Probably the same thing they did these days for Covid-19. Watching the illness spread like wildfire from one person to the other, they would have concluded that exchanges between communities, usually so dear to their social equilibrium, became in this case a mortal danger. To stop the spread, they would have secluded themselves and would have firmly forbidden any access to their village to prevent strangers from coming in. That is what a number of current ethnic groups have done because of SARS-CoV-2 and Covid-19. For example, the Kichwa and the Chicham Aents of Ecuador opted for this radical solution by blocking the routes leading to the village with large trunks of wood, ready to fight with whomever would try to break the barriers. In short, they leaned toward confinement as the first protection against the infection, as did most of the countries in the world.

However, seeing that this was not enough and that they also needed to take care of those who were sick, they would have thought to create specific pharmacopoeias. In the absence of effective Western drugs, that is what the indigenous peoples chose to do in 2020. There were discussions between shamans, scrutiny of the symptoms, trials with drug ingredients and tests on patients. They tried different types of implementation, by infusion or steam treatment, by magically extracting the ill and reciting proven incantations.

Before finding themselves on a downward slope, the indigenous peoples would probably have called on the spirits and other beings from the hereafter to get council and learn potion recipes. In short, they would have done what they knew was effective: avoid the infection, experiment with remedies, consult as many humans and non-humans as possible. In other words, they would have interacted with invisible entities and the surrounding area from which the viral danger had come from to appease the discord with nature and establish a tranquil relationship again.

ALL ROADS LEAD TO THE AMAZON

How did such an epidemic spread? Quite simply, by taking the road.

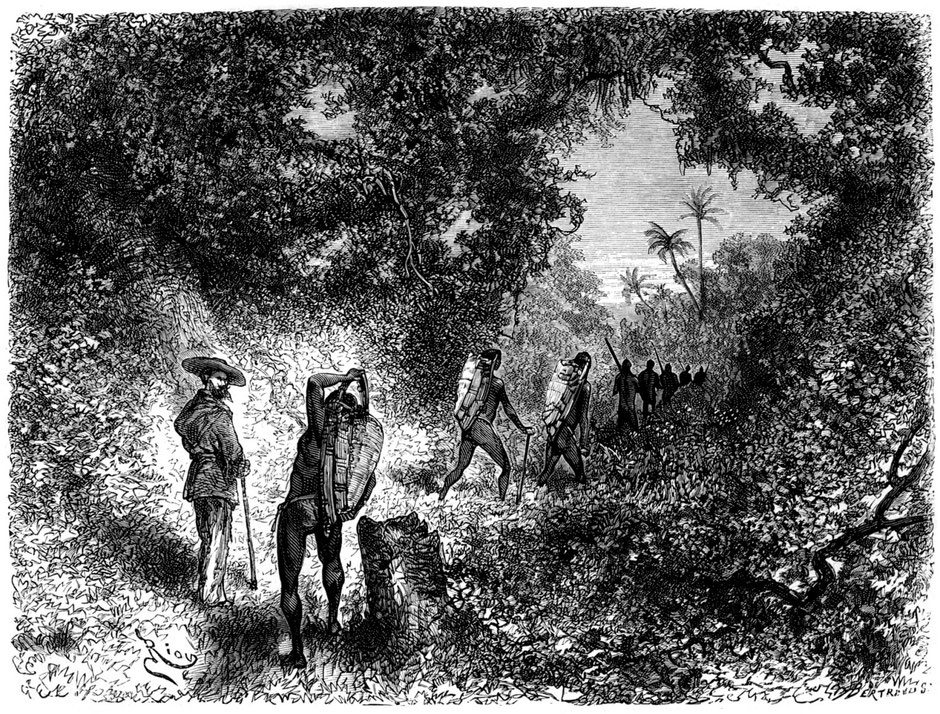

It should be noted that, contrary to the image of a tenacious Épinal, the dugout canoe is not necessarily the indigenous peoples' favorite method of travel, many of whom in fact are poor seafarers. No, the forest inhabitants are mostly unparalleled walkers. Always moving, they travel fast from one place to the other. In fact, the Amazon is littered with thousands of trails densily used, which no geo-political boundary has stopped. Another cliche that drops, the one of the impenetrable undergrownth that has to be relentlessly cut down with a machete in order to fray a vegetative path in the middle of the bramble and stinging plants. The indigenous peoples have put a carefully planned out public road system in place, that goes from the narrow winding trail to the large road perfectly laid out and cleaned up (for example, that was the case in the Xingu).

These trails mainly connect villages and have multiple uses. First of all, they allow travel and the hability to reach other settlements. It is rather surprising to see how sedentary indigenous peoples sometimes adopt a nomadic lifestyle. Any reason is good to justify an excursion: hunting, harvesting specific products, visiting parents and friends, bartering, ceremonies, fights, partnerships, etc. A meeting with someone is far from certain since there is a good chance they will be out and about.

In the past, this road network was even more developped, especially for the purpose of exchanging goods for which some were specialized in or held the secret to. The large roads were kept for specific purposes. For example, in the 18th century, the Wayana of upper Guiana had organized their country in a military fashion. They had built a large, 124 mile long road that went from north to south, separating the waters, to control the traffic on their land. A fenced village was set up every six miles, with watch towers guarded by sentinels. In this way, as soon as an alarm was given, they could quickly round up a troop thanks to the road, and confront any outside attack.

These days, on the southwest side of the Amazon, circular villages are made up of large community houses set up in a cercle around a huge ceremonial square. From these settlements radiate several trails that vary in size and use. Winding paths are used for daily activities while the very large perfectly straight roads, that can be up to forty four yards in width, are meant for ritual travel.

BARTER, BARTER, BARTER

This road frenzy was even stronger before the Europeans arrived. At least, that is what the archaeological findings clearly infer. A little bit everywhere, researchers have seen traces of a lattice of carefully built roads. These are the raised avenues crossing the flood-prone Llanos de Mojos savannas in Bolivia and those of Venezuela. In other cases, the alleyways are trenches. The most impressive ones are those of the Upano Valley, in Ecuador, that date back at least two thousand years. They can be 6 miles in width and 1.8 miles deep and stretch for miles connecting important establishments made up of artificial mounds. Quite recently, archaeologists Sanna Saunaluoma and Eduardo Neves brought to light circular sites of hills in the Acre State in Brazil, dating back to the 1300-1600 of our era, from which large roads went in all directions to join up with similar villages.

The Pre-Columbian world was thus developing a constant movement where bartering was done often and a lot. The societies were much more permeable than we would usually imagine. Inter-ethnic weddings and the integration or union of different groups was part of this dynamic. That is how new characteristics and exogenous specificities were easily adopted.

This permanent interaction could have enabled the spread of infectious diseases. A zoonosis would have used these contacts. It is likely that the outbreak of this type of infection would have terrified the inhabitants. Their first reaction would surely have been to close the roads in order to voluntarily isolate themselves and prepare a treatment. If these measures had not been effective, they could surely have escaped their lands and found another one without difficulty.

VOID WITHOUT COVID

But! I think, the indigenous peoples have had all these symptoms five hundred years ago, not with a tropical zoonosis, but with our diseases for which they did not have antibodies. The epidemiological cataclysm, they had already suffered through it with the arrival of the Europeans. The Shuar Chief Tzamarenda thus said in March 2020 in Ecuador that "pandemics have already hit us - such as the flu, the measles and chickenpox - killing millions of people in Latin America". The European conquest at the beginning of the 16th century triggered an epidemiological bomb that caused a huge chaos in the indigenous world. The demographic dropl in the first years was horrifying and it is estimated that 85 to 90 % of the Amazon populations succumbed to imported diseases.

The indigenous peoples clearly identified where the new illnesses that were oppressing them were coming from, and the link to the bartered objects they were getting from the Europeans. In the Yanomami case, Bruce Albert notes that they attributed certain epidemics to the "metal smoke", the smell of the anti-rust grease of the new machetes for which they encountered strangers, incurring a risk of contamination. Breathing in air poisoned by the exhalations of the other and having to choose to accept the peril of the disease in order to get consumable goods, there's a strange reality.

Today, the people from the Amazon are living this nightmare again, because of a lack of attention from the national authorities, with a mortality rate twice as high as that of the rest of Brazil. Susceptible to pulmonary diseases, the indigenous peoples were quickly hit by the disease, reminding them of their history's darker days with the Westerners during first contact. Furthermore, Covid-19 had a perverse collateral effect because weakened communities are no longer able to fight against the exactions of large mining groups and food-processing lobbies' henchmen. With the pandemic, the boundaries of indigenous lands have even more tragically been abused. Yet, disasters, indigenous peoples are familiar with them because, as noted by Chief Ailton Krenak in Brazil, it has been five hundred years that they have been managing the apocalypse.

Meanwhile, the Amazon is shamelessly burning, throwing a shadow on a climate threat for humanity and heralding the potential to create new pandemics.

REFERENCES

- Gibb Rory, David W. Redding, Kai Qing Chin, Christl A. Donnelly, Tim M. Blackburn, Tim Newbold & Kate Elizabeth Jones, 2020 "Zoonotic host diversity increases in human-dominated ecosystems" Nature, 584: 398-402.

- Heckenberger Michael J., Afukaka Kuikuro, Urissapá Tabata Kuikuro, J. Christian Russell, Morgan Schmidt, Carlos Fausto & Bruna Franchetto, 2003 "Amazonia 1492: Pristine Forest or Cultural Parkland?" Science, 301: 1710-1714.

- Rostain Stéphen, 2017, Amazonie. Les 12 travaux des civilisations précolombiennes, Belin, Paris.

- Rostain Stéphen, 2020, Amazonie, l’archéologie au féminin, Belin, Paris.

- Saunaluoma Sanna, Justin Moat, Francisco Pugliese & Eduardo G. Neves, 2020, "Patterned Villagescapes and Road Networks in Ancient Southwestern Amazonia" Latin American Antiquity, 31(4): 1-15.

Stéphen Rostain is an archaeologist and CNRS Senior Researcher at the laboratory "Archéologie des Amériques" in Paris. He has been working in the Amazon for 35 years, especially in Guiana and Ecuador, where he has organized several interdisciplinary and international projects, in particular using a historical environmental approach. He lately received the 2020 major archeological book award for his book "Amazonie, l'archéologie au féminin".