The COVID-AM blog is a partnership between the UMI 3157 iGLOBES and the Institut des Amériques, coordinated by François-Michel Le Tourneau, Deputy Director and Marion Magnan, researcher at the Institute. About the blog.

TO Open or not open schools: france and the us ON opposite SIDES OF THE ISSUE

January 28, 2021

by James Francis, Dean of Students at the Sonoran Science Academy in Tucson , Arizona. He holds a PhD in Transformative Leadership in Education.

by David Blanchon, Professor in geography at Université de Paris Nanterre and researcher at iGLOBES at the University of Arizona.

In August 2020, Tucson's teachers unions were protesting against the reopening of schools. This movement, led by the teachers unions close to the Democratic party, was duplicated all over the United States where close to one third of schools have not been open since Spring 2020. It could be summed up by one of the teachers like this:

"We can’t control if it’s safe for our students to come back to school, and yet we’re being told by our governor, who hasn’t cited any scientific metrics, that we should be back in school on Aug. 17 and that it’s totally okay for students, teachers, staff, to return to schools on that date." [Remarks made by an English teacher in Tucson, NPR report, July 2020]

Still at the beginning of 2021, the reluctance of most of the teachers unions to the reopening of public educational buildings has not weakened.

In France, quite the opposite, reopening schools has always been considered a priority after the first lockdown, with little push back, whether from parents or teachers unions. And the primary and secondary institutions, including preparatory courses, stayed open during the second lockdown in November 2020. This pro-opening movement, pushed by the unions considered more on the left politically, also significantly expanded against university closings.

So, in November 2020, the Snessup maintained that the educational harm would be more siginificant than the health dangers, this time with respect to universities:

"With respect to the public health plan, how can we justify the fact that universities are the last to reopen, after restaurants, after gyms...and long after stores and places of worship! As if teaching in a non-optimal long-distance method, which we were forced to put in place, fixed all the problems. As if universities were not dealing with any problems, either for teaching activities or for research activities? That is not the case. Must we repeat ourselves? The current teaching methods are having harmful psychological consequences which are likely to continue long after the public health crisis." [SNESSUP statement, November 2020]

In doing so, they were picking up Donald Trump's August 12, 2020 arguments in favor of reopening schools, probably without realizing it, with a touch of irony considering their political inclinations:

"The unintended consequences of keeping schools closed could damage our children’s education for years to come and hinder our Nation’s economic comeback. Canceling in-person classes and allowing only virtual learning disproportionately harms the education of lower-income children. During school closures in the spring, students’ math progress in low-income zip codes decreased by roughly 50% and students in middle-income zip codes fell by a third. A recent analysis found that if in-person classes don’t resume until January 2021, Hispanic, Black, and low-income students will lose 9.2, 10.3, and 12.4 months of learning, respectively." [White House statement, August 12, 2020]

As shown by these few quotes, the two countries had opposing debates on how to adapt educational policies to the pandemic, bringing to light many asymmetries between the two. In France, the leftist unions support school reopenings, in-person, with a few health measures, whereas in the United States, Donald Trump's pressure (and Republican governors) to reopen is meeting with strong resistance from Democrats and teachers unions. In the first case, reopening primary and secondary schools is still in place today despite the health situation, while in the second case public schools have often been closed right up to today. How can we explain this two-sided opposition between the two countries?

COVID-19 has been, as in many other areas, a strong indicator of the school systems, exposing a strong US decentralization which contrasts with France's hypercentralization.

IN THE UNITED STATES: EXTREME DECENTRALIZATION GENERATING DISPARITY

In the US, the president in fact has very little power on matters of education, mainly relegated to the States. But even at that level, governors have limited power, most of it being in the hands of counties and town halls. And even at that level, most of the power is given to school districts, with a Board elected by all the people concerned[1]. A school district usually oversees a city (or part of it). For Pima County, in Arizona, which has about 1 million residents, there are 13 school districts. These districts hold part of the responsibilities of France's rectorat (Board of Education), and the power of decision-making on school reopening is their prerogative, even if they received guidelines from higher level rungs.

This extreme decentralization has two consequences. First of all, the diversity of situations at all levels, between states, counties and even from one street to another. So, to date, the Tucson Unified School (TUSD) district has decided to keep the primary and secondary schools closed, while the neighboring district of Vail reopened on September 21, 2020. From one side or the other of Irvington Road, a student's situation could be different.

The second is that the school districts' position partially reflects the political composition of the district's residents. So looking at electoral cards by precinct, TUSD definitely appears blue, the Democrats' color, while Vail is deeply red and so held by Republicans. The first, more on the left, is in favor of school closures and the second, on the right, insists on reopening.

The same phenomena is happening in higher education, with their extreme decentralization and extensive autonomy, even public ones such as the University of Arizona (see this blog as an example of measures taken by a public university). There also, the University closest to Donald Trump, Liberty University in Virginia, which calls itself the greatest evangelical university in the world, publicly boasted in March 2020 of welcoming all its students in person - becoming one of the main clusters of the State the following month...at the other end, the University of California's system, which regroups all of the State's universities, such as Berkeley and UCLA, decided to close all of its campuses until Fall 2021, and move to full on-line distance learning.

In this context, the new CDC position, which now states that scientific data shows that it is possible to reopen schools if strict health measures are followed, is not likely to fundamentally change the situation in the field, as can be seen by the position taken by Chicago's teachers who decided to maintain distance learning, thwarting the district's directives.

IN FRANCE, VERTICAL POWER

This extreme decentralization highlights the contrast with France's extreme centralization, where leeway at the local level, from primary to higher education, is limited. Regulatory texts issued to personnel, invariably starting with a list of decrees and other governmental orders, show how unyieldingly vertical the system is. Local flexibility is neither planned nor authorized, even if the epidemic situation and the risks of transmitting the virus can be very different between a large university in the Paris region and a satellite university in a small town.

Excerpt of the November 16, 2020 letter to the Nanterre University personnel:

“Decree n°2020-1310 of October 29, 2020 advising the general measures needed to deal with the covid-19 epidemic during the state of emergency.

Decree n° 2020-1365 of November 10, 2020 used to apply article 20 of law n°2020-473 of April 25, 2020 on amended finances for 2020.

Memorandum of October 30, 2020 from the Secretary of Higher Education, Research and Innovation whose scope is putting a flexible lockdown in place in higher education and research.

Memorandum from the Department of Transformation and Public Service of November 10, 2020 concerning the identification and the terms and conditions for caring for public civil servants considered vulnerable."

[A flow of regulatory texts coming from the Department of Higher Education that are systematically ahead of offical texts, showing how important the French system is controlled and centralized]

Confronted with this Department's power, the unions can only be heard by issuing press releases, such as the one in the introduction, or by resorting to going on strike, and for parents and teachers by signing petitions or by protesting.

ON OPPOSITE SIDES OF THE ISSUE. SEVERAL THOUGHTS ON WHY

The public health situation is not the only reason France and the United States have taken very different positions on the issue. For example, Arizona has had a similar spread of the epidemic as France, with a delay of several weeks, including the fall-winter second wave. In both cases, the harmful consequences of school closures, especially for the most vulnerable children, were noted. In response, TUSD organized in April 2020 - the closure date - meal delivery for children who were only getting one proper meal a day at the cafeteria. In August, distribution of computers was also organized by the TUSD, with the option for some students who did not have internet to follow the courses on-line in the schools.

However, despite a clear understanding of the psychological and social risks associated with shutting classes, we can see in Arizona and in the United States in general, strong resistance from the teachers against reopening schools. On the opposite end, in France, reopening schools were considered vital and has been maintained despite the deterioration of the public health situation and the increase in restrictions of movement, while at the same time the universities remain closed for fear they will become COVID-19 clusters.

There are therefore many asymmetries between the two countries: unilateral school openings in France and a tendency to closures with a huge variety of situations in the US; an almost unilateral closure of universities in France and a tendency to reopen American universities; the left in favor of reopening many institutions in France while defending school closures in the United States...

On top of the centralization or decentralization of political systems, other elements can explain the opposing sides taken on the issue.

First of all, the extreme politicization of the issue on reopening schools has inversely played a part. In the United States, president D. Trump's and some Republican governors' stance have strongly rubbed the teachers unions the wrong way, heavily left leaning, and many residents of the school districts in Democratic areas who then pushed for schools closures for safety reasons. In France, on the contrary, fears related to a downturn in economic activity led the government to prefer a return to school in order to help parents go to work (remotely).

Secondly, the issue on COVID-19 in both countries has been "contaminated", if I may say so, by other issues. So, in the US, the teachers' long strike in 2018, centered around the demand for better pay and working conditions, is still fresh in people's mind. The option to start classes in an unmanaged public health situation could be seen as more contempt from the Republicans and as another deterioration of their working conditions, sent to the frontlines without any tools.

In France, the COVID-19 epidemic came on top of the intense debates surrounding pension reform, the Baccalauréat[2] reform and the Law on Research. The extended closure of universities, while Classes Préparatoires aux Grandes Ecoles, a French specificity and sometimes seen as an elitist symbol, remained open, was seen by some as a lack of respect for universities which have a much more diverse group of students. And the generalization of video conference classes could be seen as a way to save money in higher education, when most universities are struggling with very reduced budgets.

A recent petition from Bordeaux Montaigne University professors called "Restart classes immediately at the University" uses some of these arguments. It even pinpoints the start of the university crisis to the 2007 Law on Liberties and Responsabilities of Universities [LRU] and condemns the fact that:

"the only response from the French government has been to increase the 'digital turn' [50 million euros invested in 'hybrid learning', two million euros put aside by Bordeaux University for putting 'zoom-rooms' in place]. In order to deal with the educational and public health crisis, no serious plan of action is being considered in our country." [Petition going around at Bordeaux University]

HOW CAN WE GO BACK TO NORMAL AND OVERCOME FEAR?

While vaccination may give us hope that the situation will improve in the months to come, a return to normal is also hugely controversial. In France, it really only pertains to universities, since schools have mainly remained open. In the US, the situation is much more tense since in some States, such as Arizona, public schools have now been closed almost a whole year. The debate over whether to reopen schools or not, between parents and politicians, is therefore raging. But it often neglects one group of extremely vital people: the teachers.

New research studies are being conducted on the ability for the COVID-19 virus to spread among students. Those published by the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, show that there is a lower risk for students to contract COVID-19 while at school. This is the very argument that many proponents of reopening schools are using. According to them, students are not at high risk, and due to the lower transmissibility of the virus with younger people, schools should reopen so that students will not backslide in their education. But what many of the articles and research do not take into account is the emotional state and well being of the teachers.

According to an article posted by the Southern Regional Education Board, while colleges are experiencing an increased enrollment in teacher preparation programs, they are seeing an increasing number of early retirements and younger teachers leaving the profession. This, in addition with the teacher turnover rate and increased layoffs due to budget cuts, is leading to an increased teacher shortage. In this situation, one important factor to take into account, but difficult to quantify: the fear of being contaminated, especially if they are in a vulnerable group. Indeed, if the risk seems minor among students, this is not the case for teachers who can be elderly or have pathologies making them vulnerable. Assuaging that fear and getting back to the "new normal" is a task far greater than will be anticipated.

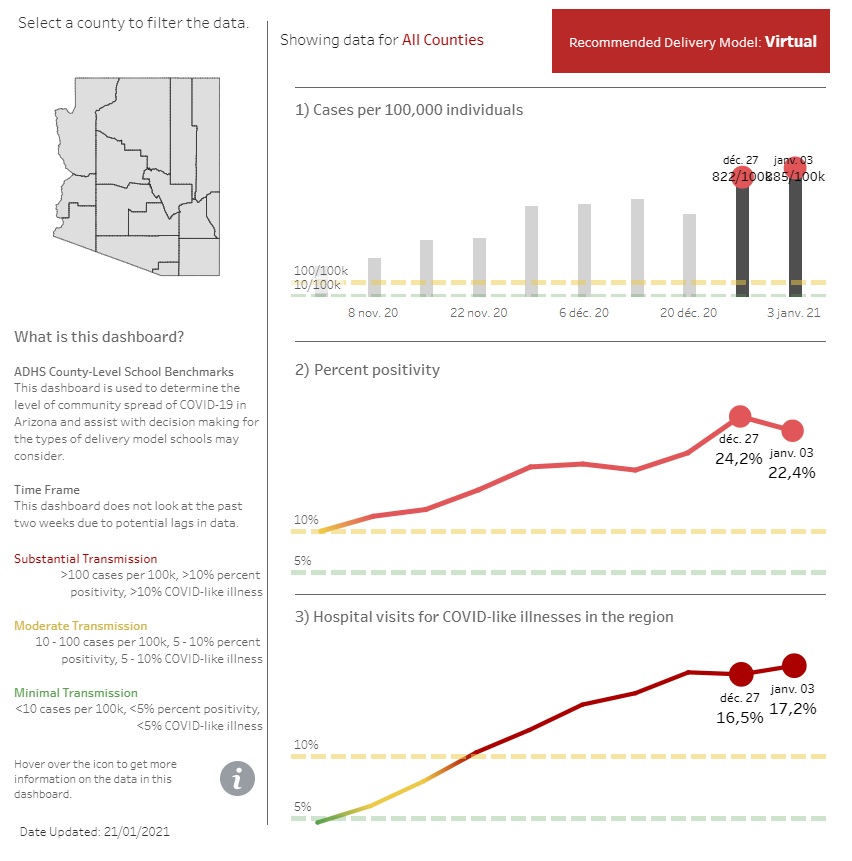

And yet, the decision to keep schools open or closed cannot be grounded in emotion, but needs to be grounded in fact. In Arizona, many of the schools use the data provided by the Arizona Department of Health Services (AZDHS) to evaluate the risks. Three major benchmarks are being used: cases per 100,000 individuals, percent positivity and hospital visits for COVID-like illnesses in the region. These three benchmarks which are broken down into individual county information help determine how the schools will operate because of the pandemic: remote learning, hybrid learning (families may choose to have their student come in for a few days a week or stay at home), or full in-person learning (schools are fully opened). For now, the benchmarks are not good enough to return to class, and the recommendation is "remote learning".

COVID-19 AS AN INDICATOR OF EDUCATIONAL SYSTEMS

In terms of education, COVID-19 seems to show opposing situations between France and the US, between a centralization on one side of the Atlantic that ignores local public health differences and an extreme fragmentation, creating disparity on the other. It also exposes each country's priorities, focused on primary, secondary and prep classes in France, as opposed to universities, a huge economic concern in the US.

But beyond re-sparking old debates, the COVID-19 epidemic has also contributed to reformulating debates, whether on the role of technical tools (computers, tablets, video conferencing software...), on the degree of autonomy of institutions or on the place given to the source (role of the parents, social reproduction, racial problem especially in the US) on the issue of educational disparity. That is why opposite sides Left/Right, Democrat/Republican do not seem understandable at first, but more logical when you take into account the organization and the recent history of educational systems.

[1] These elections are done at the same time as the general election, making the American electoral system rather complexe since each school district has its own electoral ballots...

[2] The Baccalauréat is an exam students must pass at the end of their high school years in order to graduate.

James Francis is a Dean of Students at the Sonoran Science Academy in Tucson, Arizona. He has been in the school systems for the past 12 years, previously working in Boston, Massachusetts as a school administrator and former music teacher. He holds a PhD in Transformative Leadership in Education.

David Blanchon is a Professor in geography at Université de Paris Nanterre and researcher at iGLOBES at the University of Arizona. He recently published a book on the geopolitics of water, Géopolitique de l’eau : entre conflits et coopérations, Editions le Cavalier bleu, Paris, 168p., 2019 and was one of the authors of Dictionnaire critique de l'anthropocène, CNRS Editions, June 4 2020. For more information on the topic, see article Sentinel Territories: A New Concept for Looking at Environmental Change, Metropolitics, May 8 2020.